A Decade of Regeneration.

How We Beat the Coronavirus, and the Crisis of Capitalism Too

Jan J. Zygmuntowski

Over the last decade, we have managed to repeat the greatest achievements of the 1920s. Just as, more than a century ago, technology and mass culture brought modernity to the people, the socio-economic transformation we are now completing is set to bring about a new age in human history. But it is worth recalling that the beginning of this “decade of regeneration” was an extraordinarily difficult time of uncertainty due to the coronavirus pandemic.

In the first days of April 2020, when the official number of people infected with the new virus around the world passed one million, it seemed that a worst-case scenario was imminent. Caused by inadequate sanitary control and sale of meat from wild animals at so-called wet markets in China, the unexpected outbreak of the pandemic exposed the ravages of short-term thinking by governments and businesses intent on pursuing neoliberal economic policies.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus was highly infectious and in a matter of weeks, the skyrocketing infection rate transformed it from a regional into a global problem. Some countries were able to “flatten the curve” thanks to restrictive social distancing recommendations that shut down stores, restaurants and places of worship. But years of underfunding and spending cuts or – in extreme cases – a reliance exclusively on private health care, ruled out universal testing and treatment of the worst affected patients who needed ventilators to survive.

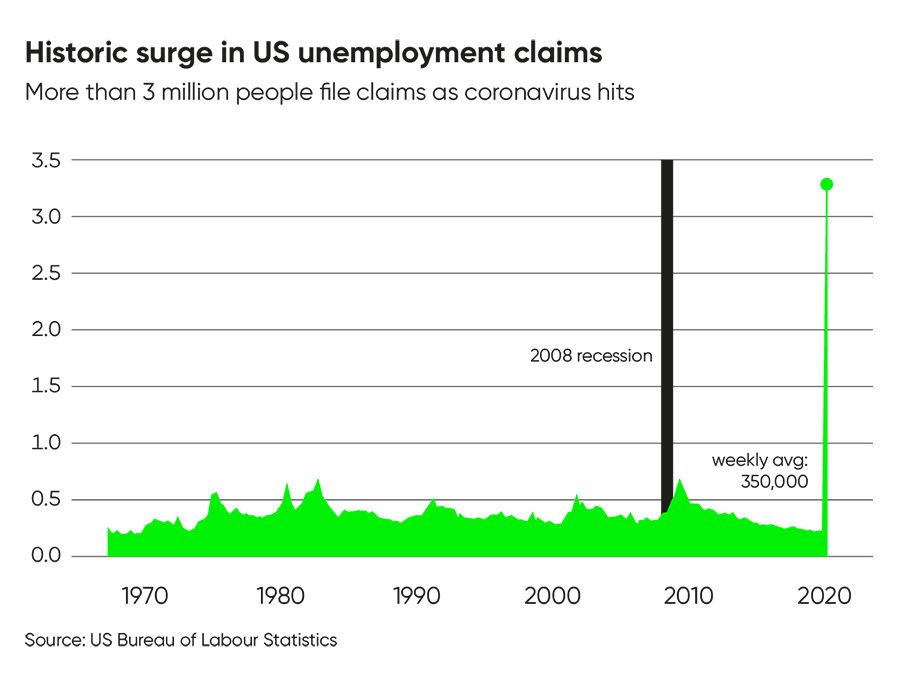

At the same time, government policies brought about an economic slowdown. This was best seen in the exponential growth of Americans registering as unemployed, with some commentators ironically comparing the bar on the chart to the wall which then President Trump had promised to build on the border with Mexico.

The crisis caused by the spread of SARS-CoV-2 became a platform for conflicting interests. In keeping with the shock doctrine defined by Naomi Klein, it was used as an opportunity to cut social spending, curb workers’ rights and bring about the controlled collapse of small and medium-sized enterprises, whose assets and market share were taken over by the largest players. Tech companies seized the chance to whitewash their image and spin their ubiquitous surveillance and value mining as “technology for good.” Shifting towards a low-emission economy to save the climate now seemed impossible.

The so-called Anti-crisis Shield adopted in March 2020 by the Polish government was designed in this spirit. Not wanting to raise public debt, a measure European governments were – despite the recommendations of many economists – reluctant to apply since the adoption of the Maastricht criteria, the scheme drained existing resources, barely providing minimum security for employees while “dismantling” their rights. As a result, the first-ever quantitative easing by the National Bank of Poland did not produce results because it failed to provide similar easing – a sweeping fiscal package that experts recommended should equal 10% of the GDP – to the people. The health care system was given pennies and businesses gained a few months’ reprieve before a wave of bankruptcies.

An Epidemic Without Shock Therapy

The arrival of yet another exceptionally warm summer in the northern hemisphere – the third hottest on record in Poland – and the severe drought that followed, together with a wave of bankruptcies and mass unemployment, caused mounting social discontent. In the United States, the crisis led to the establishment of armed militias, as demonstrators clashed with police forces throughout Europe. The line between protesting and looting became blurred, and thousands of buy to lease properties, once intended for tourists, were occupied by the homeless.

The breakthrough in Poland was precipitated by a call for a general strike by diverse workers’ groups and even small entrepreneurs. This form of industrial action, the so-called “nuclear option”, was banned at the time (only solidarity strikes in support of groups not allowed to strike were permitted). The government’s response to the strike, scheduled for September, was to announce the reintroduction of harsh restrictions, allegedly due to concerns about a second wave of coronavirus infections.

In keeping with our annual tradition, I now wish to celebrate the solidarity of all social groups, workers and others, who took part in the strike. Shutting down all schools for over a week, halting supply chains, store and factory closures, even a planned nationwide blackout, showed that not only epidemics can bring economies to a standstill.

Donations collected on the streets and on-line by social activists, a tactic that had been successfully used in the spring, helped support the groups most vulnerable to legal and economic repression. The COVID-19 epidemic finally showed us the power of coordinating and organising and allowed us to develop immunity to the virus of capitalism that had been blighting society for a long time.

The government of Poland was forced to negotiate a relief package that would thoroughly transform the country’s economy. In early 2021, the president of the Trade Unions Forum, former nurse Dorota Gardias, was appointed technical prime minister in charge of transition. The Doctor’s Cabinet, as people called the government made up, among others, of cardiologist and former health minister Łukasz Szumowski, neurologist and former senator, Wojciech Konieczny, and nurse Joanna Wicha, proposed a new social contract based on a very popular manifesto drafted by the academic community.

The Polish Regeneration

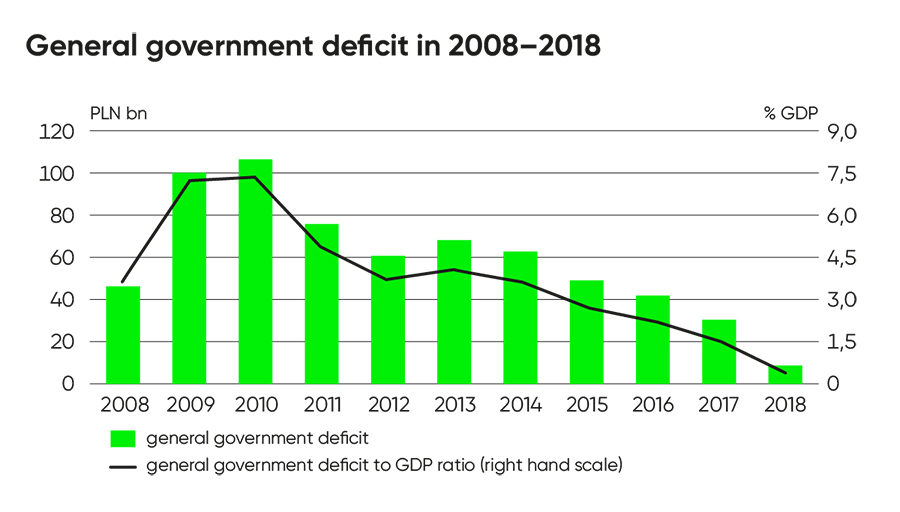

The economic miracle which The Economist would call The Great Polish Regeneration was made possible by abandoning the dogmas related to public debt and state intervention. The assumption behind this “debt arbitration” was that failure to provide greater aid would lead to a lasting crisis and, ultimately, spiralling debt. On the other hand, substantially increasing public debt might entail some risk (e.g. servicing costs), but would offer a chance for economic and social stability.

The economic miracle which The Economist would call The Great Polish Regeneration was made possible by abandoning the dogmas related to public debt and state intervention.

Poland’s national debt at the end of 2019 stood at 44.5% of its GDP. Even with the dramatic 6% decrease in GDP in 2020 and the resulting increase of sovereign debt to about 50%, the arbitrarily adopted 60% threshold was still 10 percentage points away. Historical data shows moreover that 70% of that was safe, domestic debt. The state of public finances was also better than claimed at the time by the Civic Development Forum associated with Leszek Balcerowicz, the architect of Poland’s economic transformation in the early 1990s. In contrast to that austerity programme, Polish Regeneration did not rely on shock therapy but was an opportunity for the welfare state to spread its wings.

The government ultimately adopted a fiscal regeneration package worth 250 billion new zlotys (ca. 11.3% of Poland’s GDP at the time). It relied on issuing low-interest government bonds, mobilising domestic savings (the monetary overhang was estimated at two trillion zlotys) and the redemption of these securities by the National Bank of Poland on the secondary market. As a result, Poland was able to carry out its first strategic quantitative easing and create money in line with Modern Monetary Theory. The new assets had three main purposes: 1) prioritizing health care and public services; 2) solidarity and social justice, and 3) achieving social-environmental balance.

The scheme to rebuild a public health service and the associated stimulus package have placed Poland among the world’s top countries in terms of access to health care. The regeneration budget of 2021 set public spending at 8% of the GDP (compared to around 5% for 2020), which then rapidly rose to its present level of 11%. As a result, all hospital debt was liquidated and health care has become an appealing career option for the younger generation.

The doctors and nurses, as well as technicians, paramedics and care providers who, like their peers from Cuba, now go on medical missions around the world are the pride of the nation. Transformation of the Territorial Army into the Humanitarian Corps and the reintroduction of some elements of national service is still seen as controversial, but the Corps’ successful relief effort for refugees on the Greek border during the flood of 2028 has made even critics think twice.

Support for employees and employers has also been extended, with the government pledging to keep the employment index unchanged.As in other European countries, the state now pays 75% of salaries up to twice the average wage.

Support for employees and employers has also been extended, with the government pledging to keep the employment index unchanged. As in other European countries, the state now pays 75% of salaries up to twice the average wage. In some sectors, this has been done under the heading of state aid. The state has also invested directly in some industries, and especially large enterprises, via its Economic Regeneration Facility, which acquires shares in the companies it bails out. Thanks its controlling stakes, the Facility has had a say in corporate policy: ensuring high standards of corporate governance, investment in low-emission and clean technologies, employee consultation and minimizing wage inequality. The Economic Regeneration Facility is a new type of institutional investor that uses its leverage to democratize the workplace.

A Sustainable Economy for All

One simple decision that worked was to pay out what would become today’s guaranteed income for several months and give people employed on the basis of so-called junk contracts (flexible forms of employment similar to zero-hours contracts, with no right to social benefits) access to all the privileges of the welfare state. Social benefits were extended by loosening the rules on eligibility for housing and designated benefits and removing artificially high thresholds. In neoliberal Poland, it was considered normal that only 15% of the unemployed were entitled to benefits.

One simple decision that worked was to pay out what would become today’s guaranteed income for several months and give people employed on the basis of so-called junk contracts (flexible forms of employment similar to zero-hours contracts, with no right to social benefits) access to all the privileges of the welfare state.

Already in 2022, nearly all the funding of the Institute of National Remembrance, a controversial historical institution, was transferred to the State Labour Inspectorate, thereby doubling its budget. By 2023, the Inspectorate had a uniformed enforcement branch with the power to prosecute. Abolishing junk contracts and fictitious self-employment by the end of 2024 solved the problem of precarious working conditions affecting around 2 million members of the workforce. This coincided with the appointment of the Employee Rights Commissioner, an institution that now enjoys a similar degree of esteem as the Civil Rights Commissioner.

These changes were, for the most part, welcomed by the business community in spite of the rapid decrease in social inequality and the phasing out of passive, rentier income. In 2020, the structure of the economy was based on unsustainable SMEs with little capacity for innovation. Consolidating struggling enterprises (mostly by merging them into larger, more resilient entities) and rolling out a strong fiscal package with specified strategic goals made it possible to create modern workplaces geared to the production of competitive goods for the public sector or the green industry. In light of the above, it is no wonder that the last component of the social justice model, namely switching the regressive Polish tax system over to a truly progressive one with a high personal allowance and three brackets (the highest at 45%) in 2028, also gained widespread support.

The Global Green Deal

While the Regeneration was a turning point in our history it was not entirely exceptional. Almost as soon as the crisis began, some countries like Spain and Portugal decided to implement radical relief measures by extending unconditional support to refugees and migrants. What was more surprising was the European Commission’s decision to introduce, by the end of 2020, a European wealth tax as proposed by Thomas Piketty and the Austrian Institute of Economic Research (WIFO)(levied at a rate of 1% on assets exceeding 1 million and 1.5% on assets over 5 million), and to use the annual revenue of over 150 billion euros to establish a fiscal health pact.

The US relief package, originally amounting to 2 trillion dollars (9% of GDP), partly in the form of helicopter money (basic income), and the rapid emergence from the recession of China and other Asian countries, brought the world economy back from the edge. Central banks had a unique opportunity to support the Green New Deal. Christine Lagarde, president of the European Central Bank, and Kristalina Georgieva, managing director of the IMF, agreed to make “greenness” a precondition of government bond redemption schemes (quantitative easing) and development loans.

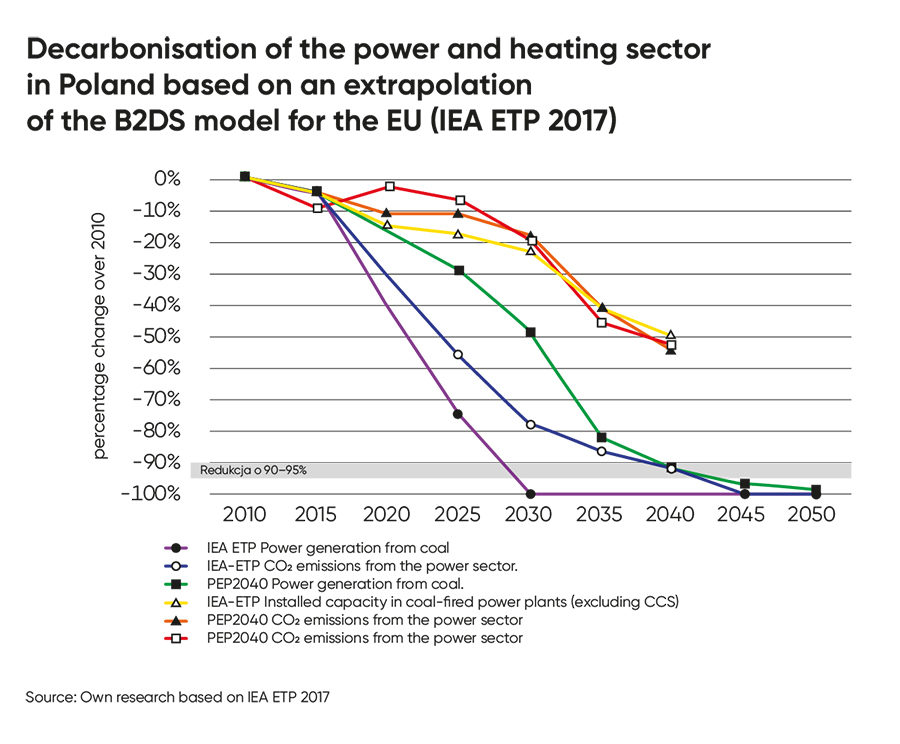

Like South Korea after the crisis of 2008, most countries decided that the lion’s share of new capital investment would be in renewables, clean technology and the circular economy. By 2026, there were 1000 nuclear power plants under construction globally, mainly small modular reactors in the emerging countries of Asia and Africa. A decade earlier it had seemed impossible that we would ever flatten another curve – that of global temperature growth – and avert the climate disaster that a 2-degree warming would trigger.

Poland also launched a vast program of energy transformation whose benefits we are partly enjoying already.

Poland also launched a vast program of energy transformation whose benefits we are partly enjoying already. The use of hydrogen fuel in transport, local government investment in rail transit systems and modernisation of the heating industry solved the problem of smog and helped achieve low emission targets. The decommissioning last year of the hard-coal fired power plant in Bełchatów and its replacement by the country’s first nuclear reactor was a milestone in the “second electrification” campaign. Along with building wind farms on the Baltic Sea, and a vast grid of smaller cooperative facilities and power clusters running on recyclables, this made it possible to eliminate coal from power and heating, almost exactly in line with the International Energy Agency scenario that we described ten years ago.

The role of social dialogue within the framework of the Committee for Just Transition also has to be recognised for finding the right way to gradually reduce employment in the coal industry with the right instruments: fixed-term financial relief and retraining programmes. An excellent decision on the part of the negotiators was getting both sides to agree that talks should be held in the spirit of intergenerational solidarity.

Regenerating the Welfare State

The last decade was a time of groundbreaking change. It proved that a socially equitable and egalitarian economy were not just possible but necessary if we are to survive.

Prioritising care for others in the wake of the real threat posed by the pandemic led society to reassess the value of various professions and services.

Prioritising care for others in the wake of the real threat posed by the pandemic led society to reassess the value of various professions and services. Today, nobody finds it strange that spending on health and education has gone up severalfold, and that nurses and teachers earn salaries comparable with middle-management positions in large corporations. The recognition of care work and social reproduction in the budget was followed by gradual improvement in the quality of public services as well as the work ethic. Consequently, the state successfully replaced market entities when it came to providing quality benefits.

Another hugely important factor was the gradual introduction of standards of teleworking and automated solutions in the public sector. Socialising data from various sources and using them in public databanks, allowed scientists, innovators and start-ups to develop new concepts benefitting from the wealth of information available. Polish telemedicine solutions, now commonplace in public health care, are being successfully exported. Instead of relying on Western technology, Poland has become an active player in the field of education, environmental protection and smart-city solutions, and its trade with developing countries is flourishing.

The modern-day welfare state whose overhaul we are about to complete had been within reach earlier. The pandemic cost millions of lives but it served as the last and most tangible reminder of how fragile our civilization is. Appealing to the imagination and opening people’s eyes to a multitude of possible futures was the key to introducing an equitable economy in 2020. It will have to continue to be so if we want to stay on the track we have chosen.

Translated by Artur Zapałowski