The Red Virus

Jonas Staal

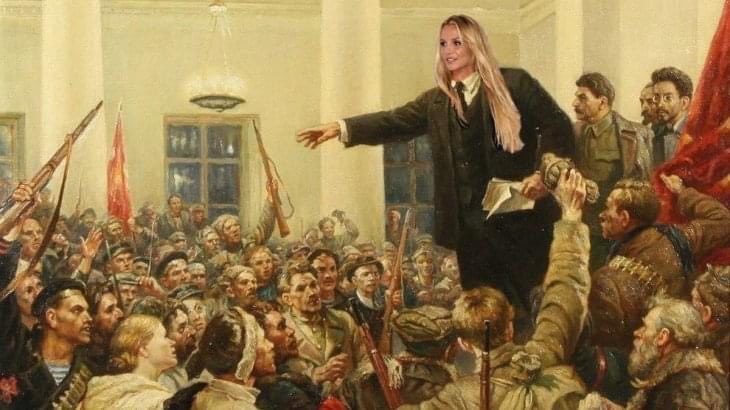

Uncredited “Comrade Britney” Meme, 2020, adapted from Vladimir Serov, “Lenin Proclaims Soviet Power” (1947)

1. Comrade Britney

In March, when the coronavirus began spreading fast in the United States, #ComradeBritney became a trending topic after pop singer Britney Spears posted an Instagram text by Mimi Zhu, a queer Chinese-Australian artist and community organizer from Brooklyn [1]. The media quickly latched onto one sentence “We will feed each other, re-distribute wealth, strike,” causing even the democratic socialist magazine Jacobin to feature an article titled “Comrade Britney Spears, We Salute You [2].” Zhu’s full text, which has sparked a wave of “Comrade Britney” memes, reads as follows:

During this time of isolation, we need connection now more than ever. Call your loved ones, write virtual love letters. Technologies like virtual communication, streaming and broadcasting are part of our community collaboration. We will learn to kiss and hold each other through the waves of the web. We will feed each other, re-distribute wealth, strike. We will understand our own importance from the places we must stay. Communion moves beyond walls. We can still be together [3].

The slogan “It’s Comrade, Bitch” – paraphrasing Spear’s famous “It’s Britney, Bitch” from her 2007 single “Gimme More” – highlights a contextual shift in which capitalist pop culture gains an unexpected critical capacity. Suddenly, the lyrics from Comrade Spears’ 1999 debut single “…Baby One More Time” read fundamentally differently. In our present predicament, we hear the first couplet’s “my loneliness is killing me” as referring to millions of people in self-quarantine, but also to our atomization and individuation under global capitalism. But the subsequent phrase, “I must confess I still believe,” emphasizes that this atomization is not a given and that the alienating and exploitative order under which we live is in no way natural. Comrade Spears’ belief (“I still believe”) thus emphasizes the necessity for political organization and unionization. This becomes even more clear when she calls “give me a sign,” which should be understood as the democratic socialist spark – a twenty-first-century specter, following the twentieth-century “specter of communism” – the collective awakening of the precariat. Closing with “hit me, baby, one more time,” now becomes a double entendre. On one hand, it articulates a threat to the system: hit me one more time – keep oppressing me, and our collective response will be relentless. Simultaneously, Comrade Britney alerts us to the fact that challenging the means of production of our terrifying reality will not come without a struggle.

The virus that has awakened Comrade Britney – the virus that gave her a sign, so to speak – is the same one that has turned millions into reborn socialists, suddenly convinced of the importance of universal health care, well-paid care workers and cleaners, and basic income.

Now, why should we take any of this seriously, considering that there are actual contemporary popular artists – from the highly politicized work of M.I.A. to The Coup – that build on the political-cultural struggle of decades past? The reason is because, in the context of our current pandemic, such moments of “going viral” pertain to a different kind of virus. The virus that has awakened Comrade Britney – the virus that gave her a sign, so to speak – is the same one that has turned millions into reborn socialists, suddenly convinced of the importance of universal health care, well-paid care workers and cleaners, and basic income. Here we witness the spread not of a physical infection, but of an idea, which consists of a series of egalitarian principles through which we can confront and collectivize our present [4]. This red virus, to which even the former Britney Spears is not immune, spreads new forms of egalitarian life.

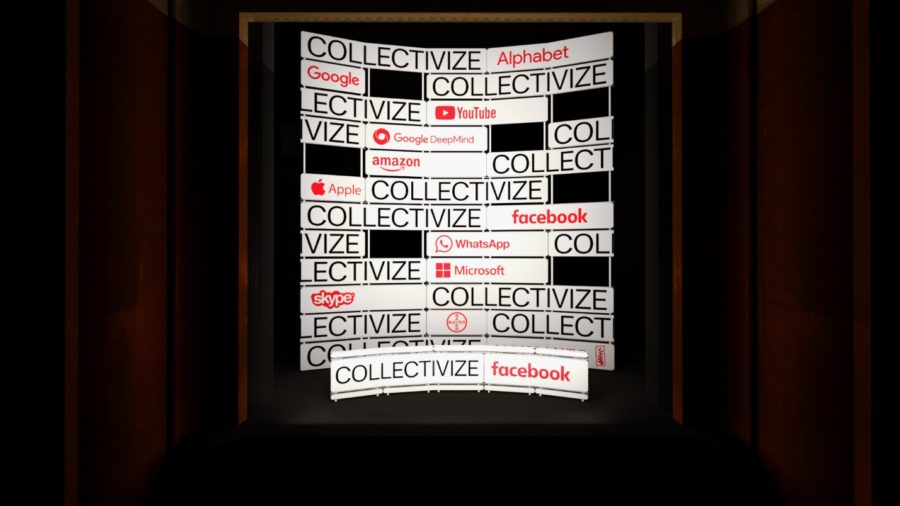

“Collectivize Facebook” (2020), Jonas Staal and Jan Fermon

“Collectivize Facebook” (2020), Jonas Staal and Jan Fermon

HAU Hebbel am Ufer, Berlin. Image: Remco van Bladel and Jonas Staal

2. Going Viral

Obviously, the red virus is far from the only ideological trope trying to overtake the “master narrative” on how to interpret the origins and consequences of the current coronavirus crisis [5]. Ultranationalists and the alt-right see this as a chance to double down on their call for border walls and other fortifications, shamelessly equating migrants and refugees with the virus. Transnational corporations are lining the halls of congress and the European Central Bank for fresh handouts and bailouts. Big Pharma, the securitization industry, and “flash traders” see their chances to ruthlessly profit on the deaths of, potentially, hundreds of thousands of people. And a dangerous belief is taking hold, pointed out by Sherronda J. Brown, that humans themselves are the virus as if this pandemic were nature taking its revenge on us [6].

Those who tell us not to “politicize” the coronavirus crisis aim to do so in order to naturalize their own ideological narrative as constituting the “new normal” to which to return. But this supposed return to normality – mimicking nostalgic slogans such as “Make America Great Again” (a return to a sovereign nation that never was) or the notion of the “post-truth” era (a return to the pre-Trump era from which we inherited the nightmare of global capitalism) – is not a solution, it is precisely the problem. The fragility of global capitalism and its structural inequalities is further exposed by the pandemic, leading to desperate attempts by transnational corporations and neoliberal governments to restore this deeply unsustainable system. The very machine that undid our future (wait for the climate crisis-fueled pandemics yet to come) now manically tries to spread the notion that it can save our present. What is not political about this process? We have not a moment to spare in setting the conditions for our red virus to go viral and call liveable forms of life into being. As Donna Haraway noted, pre-pandemic: “I’m really interested in propaganda as a form that need not be full of alt-anything, that can be a practice of collecting each other up and telling important truths with certain kinds of tonalities [7].”

Art and culture play a crucial role in the process of propagating such “important truths,” which we should understand in terms of a propaganda struggle: a battle of infrastructures, narratives, and imaginations that shape our past, present, and future.

Art and culture play a crucial role in the process of propagating such “important truths,” which we should understand in terms of a propaganda struggle: a battle of infrastructures, narratives, and imaginations that shape our past, present, and future [8]. The red virus delineates the battle lines between those infected by a vision of new shared forms of resilient, egalitarian life and those who believe a continuation of murderous global capitalism is the cure, rather than the source of our misery. It is through such a delineation that we articulate a space of comradeship, in Jodi Dean’s words: “toward the sameness of those fighting on the same side [9].” The red virus thus creates a reverse kind of infection: it does not leave us to our own survival, every individual for her- or himself, but it makes us more the same (which is not to deny the violent class differences that are only more aggressively made manifest in our pandemic present) [10].

But how to propagate when the preferred means of emancipatory politics, such as the assembly, become impossible due to self-quarantine, a condition in which we see the atomization and individuation of global capitalism fully manifest in our day-to-day choreographies – that is, if you are even privileged enough to be able to self-isolate and “social distance.” What does it mean, in these conditions, to say, as Mimi Zhu does, that “we can still be together”?

“TRANSUNIONS” (2019), Jonas Staal, produced by Biennale Warszawa

“TRANSUNIONS” (2019), Jonas Staal, produced by Biennale Warszawa

Photo Jonas Staal

3. Collectivization as Assembly

This past year, I was working with lawyer Jan Fermon on an indictment against Facebook, titled Collectivize Facebook. Together, we conceptualized what we call a “collectivize action lawsuit”: a court case with thousands of co-claimants. Our aim is to engage in a concrete legal struggle to enforce the recognition of Facebook as a public domain, and subsequently as public ownership while organizing collective gatherings to discuss what we would do once we win. I know, the notion of “winning” is rare in emancipatory political discourse, as we have come to adopt Samuel Beckett’s famous line from Worstward Ho (1983) as a mantra: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” Of course, Beckett’s words challenge us to think beyond the doctrine of the win-lose dichotomy, a linear winner-takes-all mentality inherently tied to the (self)exploitative system we must abolish. But is a form of collective winning – as trialled in practices of cooperative gaming for example – not also a way to overcome this dichotomy? And is it not for the fear of repeating the tragedies of real existing socialism that we have come to fetishize failure as a kind of tragically heroic gesture – a guarantee we succeed (at our failure) while shedding the responsibility to affect real change?

Fermon and I aim to organize what we call “pre-trials,” which will lead up to submitting our indictment at the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva. These pre-trials are preliminary procedures in which we present and discuss the indictment in order to gather more co-claimants, while simultaneously calling upon the collective imaginary to begin shaping the world after our victory. If we can turn Facebook into a transnational cooperative of 2.2 billion active users, how will we collectively govern it? Will we vote for a new social contract, or install a transnational people’s committee to oversee this socialized social media? Do we ban the storage of data, ensure encryption and privacy to all, forbid any form of advertisement, and compose our own algorithms as a form of comradely Artificial Intelligence, rather than as an invisible force that further fortifies our individual echo chambers [11]? A collective exercise of shaping the worlds we can still win, but simultaneously an exercise in overcoming our fear of collective governance – a fear that might have sound historical justifications, but that has led us to abandon the infrastructures through which our struggle can propagate and construct new egalitarian realities.

When the coronavirus began to emerge worldwide, holding the first pre-trial – which was to take place on March 26, 2020, at the HAU Hebbel am Ufer Theater in Berlin – would have been irresponsible. And if half the world was not being streamed already, the pandemic certainly made sure of it: corporate social media has spiked, Zoom installed on nearly every home office computer, theatre and discussion programs hooked to Youtube channels and Facebook live streams. There are two sides to this development. The first is possibility, the desire to shape new forms of culture in the crisis, create new forms of nearness, with the significant consequences that more cultural institutions have moved to open-source shared content than ever before. The second is the risk of maintaining a criminal normalcy, with teachers finding themselves made to work even more low-paid hours on Zoom than before, cultural workers paid even worse, office meetings dragging on endlessly, as if this pandemic was just a massive corporate exercise to explore how to make budgets even leaner than they already were. Those who can claim some form of cultural capital in the digital world benefit; those who do not (if they have access at all) have lost yet another way to maintain their precarious survival. But this was precisely the reason for still launching our Collectivize Facebook campaign, for as our dependency on corporate “social” media and monopolized tools of communication increases in this crisis, so is the need to challenge their means of ownership. The red virus must contaminate these new digital sites of struggle, and the material infrastructures that sustain them.

Fermon and I claim that the current model of ownership of Facebook fundamentally undermines people’s and individuals’ right to self-determination, as enshrined in various international human rights treaties – while we are, of course, well aware of the deeply problematic liberal and individuated meaning of this emphasis on the “human” in human rights [12]. Facebook has turned us into neo-feudal data workers, profiting off our data without compensation, while making us increasingly dependent on the platform – Amnesty International even calls Facebook “inevitable [13].” The corporation is further implicated in its surveillance of its users, not only through “shadow profiles,” but also by sharing information with governments, possibly endangering dissidents’ and activists’ lives, and by enabling companies such as Cambridge Analytica to collect data from millions of users’ profiles. Facebook wilfully advises authoritarian regimes, such as that of Duterte in the Philippines, which now uses the platform as its main organ of public communication. But of course, these arguments – which sustain the larger human rights violation that is Facebook – apply not merely to this corporate giant alone, but to various other trillion-dollar companies as well.

The question we now face – which has gained additional urgency in the context of the coronavirus crisis – is what forms of life the red virus can propagate into being. Not forms as we have known them, which leave us only to decide between strengthening the power of the nation-state or those of private capital, or – more often than not – deeply entangled combinations of the two. Our common crisis goes well beyond the borders of the nation-state, but the borderless transnationalism of high-finance capitalism represents nothing of the redefined internationalism that we need at this moment [14]. Would a strange hybrid between the two, a cooperatization – a making collective – of the transnational corporation become an imaginable form exactly at this moment of crisis? The liberal former presidential candidate Elisabeth Warren has already called to “break up Facebook” [15], while ideas for the nationalization of Amazon are gaining ground as our self-isolation only further expands its already vast monopoly [16]. And so a propagation – a replication – ensues, Collectivize Facebook, Collectivize Alphabet, Collectivize Amazon, Collectivize Apple, Collectivize Microsoft, Collectivize Bayer…

This moment we find ourselves in, where unexpected comrades crop up and where the reasons for our brutal precarization become increasingly visible, is one where we can assemble through collectivization rather than through the immediate nearness of our bodies.

In self-isolation, we miss the assembly, but maybe there was also something missing in the assembly itself. Of course, reducing the vastly different practices and scales of precarity and urgency that underlie what Judith Butler has termed “performative assembly” would be undesirable [17], but at least in my own experience – from the Occupy movement to the Amsterdam University occupations, as well as in my own organizational art practice, ranging from the alternative parliaments I developed in the New World Summit to the transnational New Unions campaign – there has been a recurring risk of relying on the rather liberal idea of the so-called “wisdom of the crowd.” The danger is in an opinion-driven, rather than a principle-driven propagation. This moment we find ourselves in, where unexpected comrades crop up and where the reasons for our brutal precarization become increasingly visible, is one where we can assemble through collectivization rather than through the immediate nearness of our bodies. It is this assembly of the means of production and communication which, when cooperatized, allow our renewed comradeship to manifest into new forms of life.

* * *

[1] Katherine Gillespie, “Meet Mimi Zhu, the Socialist Who Convinced Britney to Join the Cause,” Paper Magazine, March 25, 2020: https://www.papermag.com/comrade-britney-mimi-zhu-interview-2645576691.html?rebelltitem=2#rebelltitem2.

[2] Dawn Foster, “Comrade Britney Spears, We Salute You,” Jacobin, March 25, 2020: https://jacobinmag.com/2020/03/britney-spears-coronavirus-strike.

[3] These and other text-based works can be found on Mimi Zhu’s Instagram official Instagram account, https://www.instagram.com/mimizhuxiyuan/.

[4] See also: Jonas Staal, “Coronavirus Propagations,” e-flux conversations, March 17, 2020: https://conversations.e-flux.com/t/coronavirus-propagations-by-jonas-staal/9671.

[5] Terence McSweeney, The “War on Terror” and American Film: 9/11 Frames Per Second (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), p.10.

[6] Sherronda J. Brown, “Humans are not the virus, don’t be an eco-fascist,” Wear Your Voice, March 27, 2020: https://wearyourvoicemag.com/news-politics/humans-are-not-the-virus-eco-fascist.

[7] Transcribed from a lecture by Donna Haraway, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, March 25, 2017: https://vimeo.com/210430116.

[8] See further: Jonas Staal, Propaganda Art in the 21st Century (Cambridge/London: The MIT Press, 2019).

[9] Jodi Dean, “Four Theses on the Comrade,” e-flux journal, #86, November 2017: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/86/160585/four-theses-on-the-comrade/.

[10] Arwa Mahdawi, “The coronavirus has exposed the truth about celebrity culture and capitalism,” The Guardian, March 31, 2020: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/mar/31/the-coronavirus-crisis-has-exposed-the-ugly-truth-about-celebrity-culture-and-capitalism.

[11] On AI and “other intelligences” see James Bridle’s lecture, “Other Intelligences,” HAU Hebbel am Ufer, March 19, 2020: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-S3rJnTxFoY.

[12] See: Radha d’Souza, What’s Wrong with Rights: Social Movements, Law and Liberal Imaginations (London: Pluto Press, 2018).

[13] Amnesty International, “Surveillance Giants: How the business model of Google and Facebook threatens human rights,” Amnesty International, 2019: https://www.amnesty.be/IMG/pdf/surveillance_giants_report.pdf.

[14] Kuba Szreder, “Independence always proceeds from interdependence: A Reflection on the Conditions of the Artistic Precariat and the Art Institution in Times of Covid-19,” L’Internationale Online, https://www.internationaleonline.org/opinions/1021_independence_always_proceeds_from_interdependence_a_reflection_on_the_conditions_of_the_artistic_precariat_and_the_art_institution_in_times_of_covid_19.

[15] Lauren Gambino, ‘Too much power’: It’s Warren v Facebook in a key 2020 battle,” The Guardian, October 20, 2019: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/oct/19/elizabeth-warren-facebook-break-up.

[16] Paris Marx, “Nationalize Amazon,” Jacobin, March 29, 2020: https://www.jacobinmag.com/2020/03/nationalize-amazon-coronavirus-delivery-usps.

[17] Judith Butler, “Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly”, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015).