Transunions

Jonas Staal

- The Crisis of Imagination

The crisis of the European Union is being explained to us as a political crisis, as an economic crisis, and as a humanitarian crisis. These descriptions are accurate, but they seem to overlook a more structural crisis that underlies them: the crisis of imagination.

A recurring tendency in art discourse is to describe the political importance of art in terms of the imagination. If we cannot imagine a different future, how could we ever act towards such a future politically? In this line of reasoning, artistic imagination might even precede political action. But there seems to exist a second dimension to the crisis of imagination that is less often invoked, namely the lack of imagination when it comes to understanding how devastating our present actually is, how little change the stakeholders of our reality are willing to accept, no matter how many alternative imaginations we confront them with, and no matter how “realistic” or “democratic” these alternatives might be.

This dual crisis of the imagination—a lack of imagination to understand our disastrous present as much as to project our desired future—is best illustrated through the Brexit dichotomy. One side of this dichotomy is defined by the Leave camp, an amalgam of opportunist Tories and racist ultranationalists, and consists of the projection of a mythical past, fueled by a residual sense of superiority of a decaying Empire. The other side of the dichotomy is defined by the Remain camp, led by the Eurocratic elite, who propose the continuation of what they consider to be the proven formula of brutal austerity politics, in the guise of liberal democratic reform. Neither the Leave nor the Remain camp seems to grasp that what they propose as a return to the past or continuation of the European cartel’s business as usual does not form a competent answer to the devastating crises that we are facing. The endless renegotiations of Brexit, with the aim to maintain a global market while staging a separation, will only deepen the disillusionment of the Brexiteers. The continuation of the austerity doctrine will just as well deepen existing inequalities and the further erosion of whatever remains of the right to self-determination of EU member states, creating the conditions for the Nationalist International of Wilders, LePen, and the rest of their cronies to gain strength.

The Leave and Remain camps are positioned as opposites, but actually they rely on one another fundamentally. The Eurocrats’ austerity politics, a euphemism for economic terrorism, fuels the desire for a “return” to national sovereignty under the by now famous Brexit banner “Let’s Take Back Control!” Simultaneously, the rise of the ultranationalists has reenergized pro-European forces; compared to the racist and violent future-pasts they propose, the status quo of the austerity elite suddenly comes across as salvation. As such, the Leave and Remain camps form two competing factions in the same hostage situation: either way we choose, we will inevitably support the legitimacy of the other. In order to reclaim not our borders but our political imagination, it seems essential to reject both options and stand firm on the demand of a third, fourth, or fifth option to come.

Both the Leave and Remain camps address the crisis of the European Union, either through a prolongation of the present (Remain) or as a return to a mythical national sovereign past (Leave). In both scenarios the imaginative category of the future is absented in addressing the organization of our present. So how can we stand firm in the face of Brexit and say, “I prefer not to,” while instead engaging a propositional future—the third option, or “third space”? Is a Parallel Union, a Transcontinental Union, or a Transunion not within the grasp of our imagination? And if the imagination is indeed the site of struggle for artists and cultural workers, what propositions have they contributed in order to imagine our disastrous present, as much as desired futures?

2. Unionizing the Imagination: Past, Present and Future

Art and politics are not the same, but they do create the conditions for each other’s manifestation. Political literacy and visual literacy influence one another greatly. Artistic imagination can contribute to the morphologies of alternative futurities, while politics can enable infrastructures to turn these imaginaries into material reality. In the best cases, emancipatory art and emancipatory politics author each other into being, and construct a new reality through one another’s competencies. This is important for artists and cultural workers that wish to contribute to the imagination of a new transnational politics to break through the hostage situation imposed by the Brexit dichotomy: we do not and should not imagine new worlds from scratch, but learn from and contribute to the imaginaries that have been tirelessly build, theorized and programmatically articulated by popular mass movements, pan-European platforms and emancipatory political parties, sometimes over a period of decades. Thus our challenge is to develop the symbols and narratives – the visual morphologies – that unionize these various imaginations into a new transnational assembly.

Site-specificity is, in this context, a crucial aspect. For the Transunions assembly that takes place June 22, 2019, as a collaboration between my New Unions campaign and the Warsaw Biennale, this concerns the Palace of Culture and Science in Warsaw, which was “gifted” to Poland by order of Stalin as a symbol of internationalism, exemplified by the surrounding sculptural reliefs that represent revolutionary, proletarian workers from around the world. Obviously, there should be no present-day desire to provide any retrospect legitimacy to the murderous Stalinist regime which turned the idea of internationalism into an authoritarian management of proxy regimes and parties, reinforcing Stalin’s own ideological betrayal of the revolution in the form of his “socialism in one country.” The Palace of Culture and Science monumentalizes an ossified internationalism, although it must be said that in the reality of the policies of communist Poland, it did actually exist. From the Cold War onwards, Poland – in its alliance with the Soviet Union – invested substantially in post-colonial nations of North-Africa and the Middle East. Polish architects, planners, engineers and artists traveled abroad to develop infrastructures such as the fair area in Accra, the master-plans of Baghdad, Algiers and the region of Tripoli as well as housing neighborhoods in Iraq, Libya, and Syria.

The site where Transunions take place thus embodies something of a historical dilemma: Stalinism must remain in the dustbins of history, but the internationalist heritage it appropriated and squandered – and of which the monumentalized workers guarding the Palace continue to remain witness – should be recuperated. The hard turn to ultranationalist and alt-right parties today across the European continent, would benefit from being reminded of the major achievements that international cultural exchange brought about, in seeking for a new common language of a new world in the making. And while the Comintern was brutally weaponized, the lack of a Transnationale today shows its disastrous consequences: authoritarian-capitalist states pursuing aggressive foreign policies dominate transnational trade and military agreements, and subsidize corporate actors that disproportionately influence our political and economic life. This leads to terrifying situations in which the Rojavans, who bravely fought and sacrificed to protect their multiethnic and multireligious region in North-Syria against the Islamic State while establishing their own feminist democracy in the process, are forced to ask support from the Trump regime as the Erdoğan dictatorship threatens with their massacre. As Kurdish Women’s Movement activist and thinker Dilar Dirik argued, that would be the moment to call upon a “Left Air Brigade” – but in the post-Comintern world, there is no such thing.

All of these questions – including the last, complex issue on how a transnational union deals with the question of power and international solidarity – are embodied in the very material infrastructure of the Palace of Culture and Science. A ghost of internationalism, that stands both for all that is to be rejected, and all that is to be gained from re-engaging these fundamental questions if we aim to make a future of emancipatory governance possible. Therefore, unionizing the imagination does not mean abolishing the past, but inviting history as an actor to the assembly, to debate and listen to it, to learn from it and reject some of it. A genuine assembly does not only include humans of the here and now, but also the past, the present and the future.

3. Pre-enacting our Transunionized Future

One of the many things that the participation of this particular internationalist history in the Transunions assembly can tell us, is that in the process of challenging the Brexit dichotomy to articulate our third, fourth and fifth options, we might benefit more from investing in the idea of the “Union” rather than in that of “Europe”. In other words, transnational unionization is not the same as transnational Europeanization, of which we have already witnessed the consequences in the disastrous colonial empires of the past. What Poland’s past internationalism can hint at, is the possibility of transcontinental unionization, from the Middle East to North-Africa and Europe.

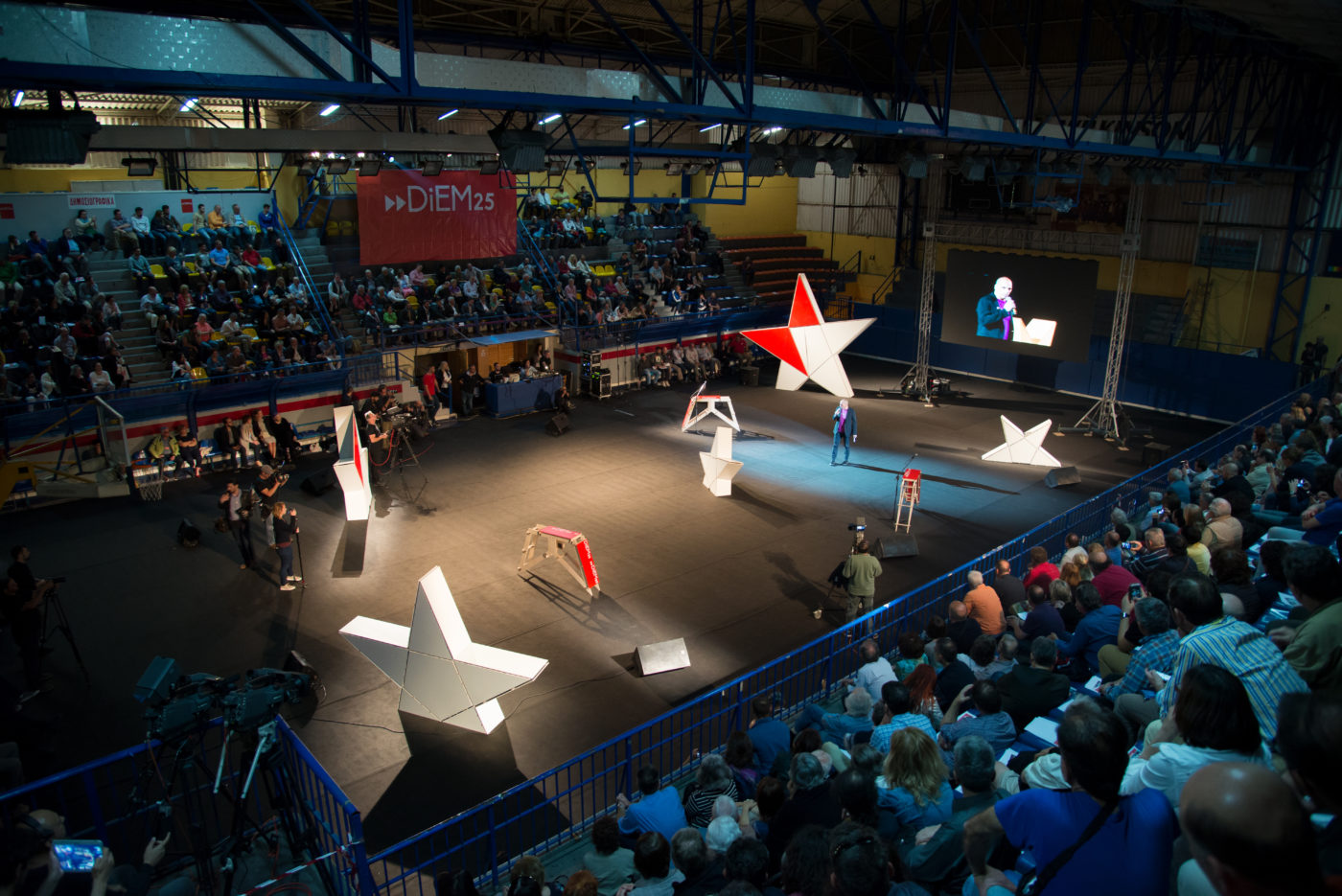

This is why the Transunions assembly has aimed to gather various organizations from across continents involved in theorizing, mapping and practicing new models of emancipatory transnationalism in the fields of politics, economy, ecology, education and culture, striving to establish new models of planetary egalitarianism. This includes the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO) that forms an alternative to the present-day UN, the African Cultural Policy Network that develops cultural infrastructures across the African continent, the Kurdish Women’s Movement that promotes an alternative model of stateless world confederalism, the Democracy in Europe Movement 2025 (DiEM25) that aims to democratize the EU towards a progressive federation, and the Transnational Institute which has for various decades developed a multifaceted understanding of transnational democracy.

Articulating our third, fourth and fifth options beyond the discussed dichotomy thus begins with abandoning Europe as the cultural category that would articulate a new social contract for transnational unionization. Instead, it seeks for other common pillars, such as the democratization of politics, economy, education and culture, combatting offshore tax havens, prosecuting climate criminals and turning corporations into cooperative models under the precariat’s control. Unionizing the imagination of transnational politics, simultaneously means unionizing a new transnational social contract that emerges from a common understanding of the intersections of collective conditions of oppression, which might be more severe in one region than in another, but very often can be traced to the same sources of exploitation of labor, culture and ecology. The ultranationalist state, the transnational corporation, or the most disastrous intersections of the two, must both be abandoned simultaneously for transnational unionization to establish a new emancipatory hegemony.

From an artistic point of view, the challenge is to transform the sites of the internationalist past to those of a transnationalist future. To imagine the new infrastructures and symbols of transnational parliaments, to reorganize the stars of austerity of the flag of the European Union and unionize them into a new whole, to build on the emancipatory monochromes of red, purple and green, that have formed the visual and ideological horizons of emancipatory politics, feminism and radical ecology. From the archeologies of past-futures, our re-constructivism seeks to enable,– visually and materially, infrastructures of our future-present. This is what Transunions aims to do, to propose an alternative site of assembly through insurgent symbols of a new transnational, where emancipatory political platforms can gather to pre-enact the future in the present. To show that, if we can imagine a transnational future in the present, if we can identify new representatives and propose new choreographies of a transnationalism to come, then the seeds are planted for it to turn into political, tangible reality.

The power of imagination can enable a trajectory into futures that previously were unthinkable. But once we can think it up, once we liberate the force of collective imagination, we enable our capacity to realize the union of many unions that we so desperately need.

×

The first section of this essay was previously published as part of the text Let’s Take Back Control! Over our Imagination, by Mihnea Mircan and Jonas Staal, Stedelijk Studies, #6, Spring 2018.