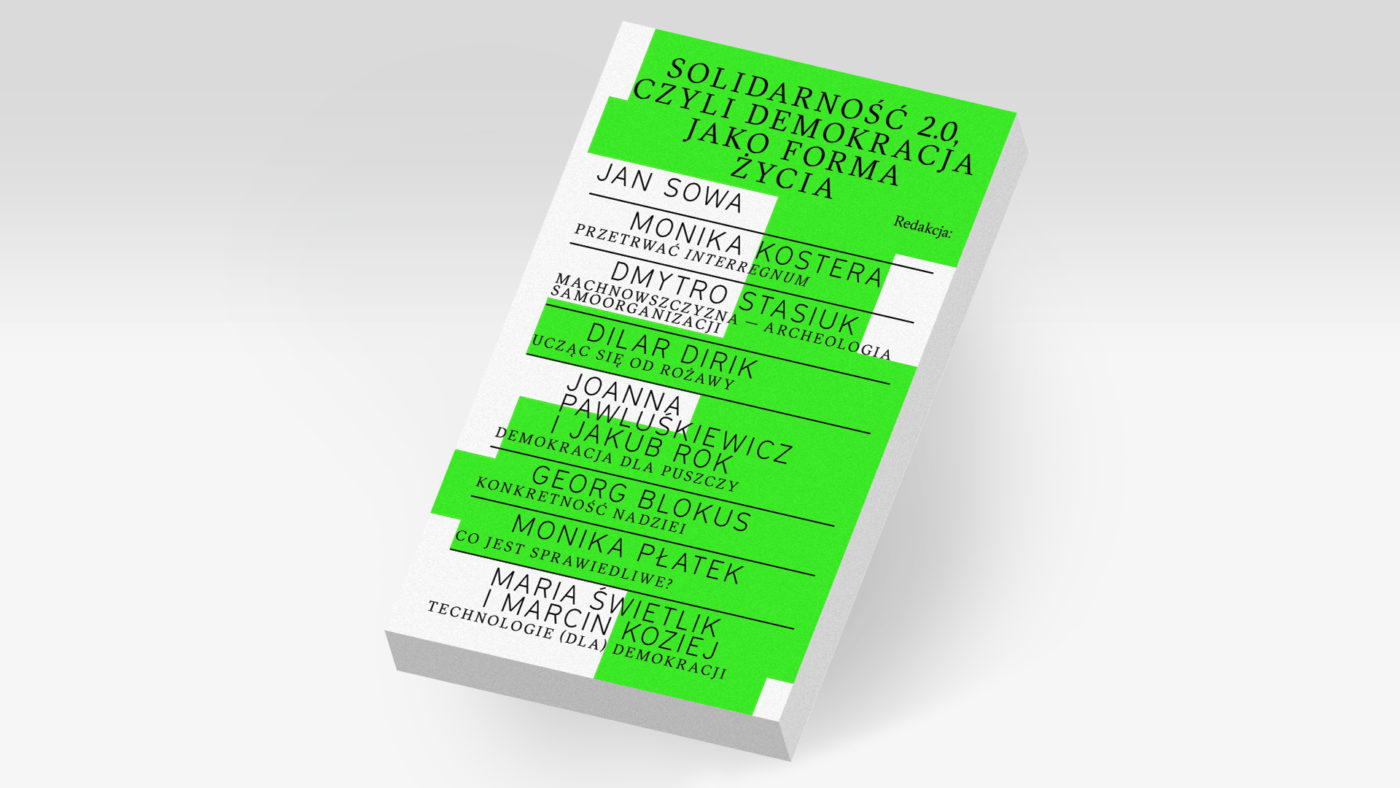

Solidarity 2.0, or Democracy as a Form of Life

A book edited by Jan Sowa available in bookstores

Despite the obvious crisis of political representation, reflection on democracy and attempts at its practical development are currently rather stunted. The liberal centre, scared to death of the populist revolt, remains trapped in the imaginarium straight from the 1990s, when such abstractions as “civic society” or “freedom” were eulogized and considered an immovable foundation of modern politics. Although hardly anyone today believes Fukuyama’s famous bon mot about the end of history, liberal journalists and theoreticians act as if parliamentary democracy was an ahistorical model of democratic society cast in platinum of civic virtues and deposed in the political equivalent of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures in Sèvres. Meanwhile, there are not many thing as useful for driving the populist-conservative-fascist revolt as defective mechanisms of political representation. They make significant segments of the population feel excluded from the participation in the political life, and extremely disappointed with the behaviour of mainstream politicians. Hence the anti-establishment attitude common to various strands of populism and the related tendency to elect politicians who do not fit into the moderately “reasonable” format pushed by the liberal centre. This book, presenting a radically democratic alternative to contemporary parliamentary politics, constitutes a voice in the discussion on the possible solution to the crisis of democracy in which we are nowadays deeply immersed.

Excerpt from the Introduction by Jan Sowa

Solidarity 2.0, or Democracy as a Form of Life proposes the perspective of expanding and shifting the consideration of the socio-political condition of contemporary societies by looking at their very foundation – democracy – slightly sideways: the axis of the reflection he suggests is marked not by the political present day, i.e. the reality of parliamentary and representative system, but the conviction that democracy is a certain form of collective life with the acknowledgement of the political power as the common good at its base. Liberal parliamentarism presented in this light turned out to be only one of the possible methods of the democratic organisation of power and, contrary to popular belief, not the most democratic one.

In the book, this perspective becomes the starting point for conversations with people directly involved in self-organised, democratic initiatives, or dealing with their systematic study: in seven interviews issues of the contemporary Rojava (Kurdistan) meet Nestor Makhno and his Free Territory of the Ukrainian grasslands at the beginning of the 20th century, the Camp for the [Białowieża] Forest meets Occupy and Indignados movements, organisational art meets the utopias of digital democracy, and the collectivisation of cultural institutions meets the workers’ democracy and restorative justice.