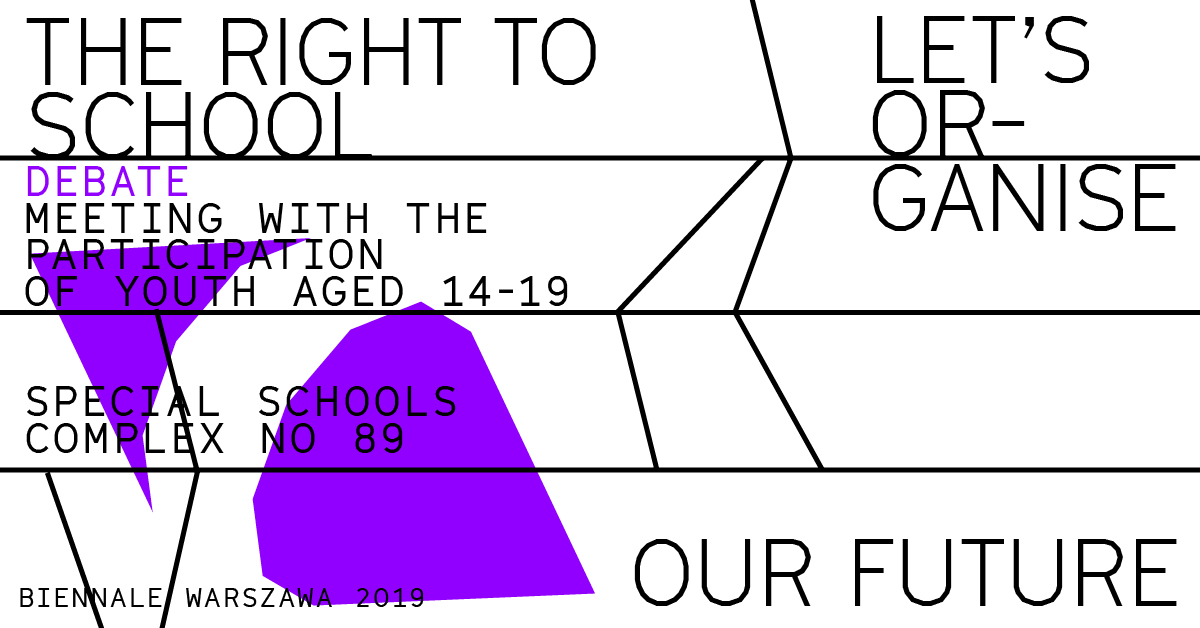

The Right to School

Meeting with the participation of youth aged 14-19

Who does the school belong to?

Who designs schools? Who writes core curriculums and textbooks? Who determines regulations, timetables and everyday rules of functioning in schools? Who sorts the children according to their address, age, gender and intellectual abilities? Who does the assessment? Who organises entertainment and creative activities? Who decides about clothes, food, physical activity, the colour of walls, library purchases, and every other aspect of life in schools?

And why it is not the students?

Why adults disregard the voice, ideas, feelings and the perspective of children and young people?

Who are the students? School’s customers? A raw material to be processed? Imperfect adults who need to be shaped?

It is a common belief that the school is a place where teachers have the power and parents’ legitimization to maintain this type of relationship with the use of the advantage of knowledge and experience, persuasion, the principle of respecting your elders, imposing values and norms, and sometimes also fear. All these strategies are founded on the idea that this asymmetry is obvious. How can democracy, children’s and human rights be learned in such a school setting?

Who then – almost one hundred years after the writings of Janusz Korczak – seriously believes that a child’s subjectivity, inscribed in various documents concerning Polish education, is worthy of being exercised in practice?

As this catalogue goes to press, the strike of Polish teachers, fighting for the improvement of working conditions in public schools, is still ongoing. The salaries of people who share the responsibility for raising children, and thus are directly responsible for the future of our country and the world, are criminally low. Subsequent reforms of the education system are not oriented on instilling civic awareness and tolerance in young people, and they do not fully develop their intellectual and creative potential. Discussions around the shape of the school – teachers’ work conditions and core curriculums – are in the heart of the current political debate.

But each discussion lacks an important, if not the most important voice: no one asks children and youth how they imagine the school of which they would like to be a part.

The debate will be held in the form of a Long Table. This mode of discussion was conceived by an Amercian feminist collective Split Britches. The idea is to create the conditions for a democratic conversation that would not be moderated, which makes all the participating voices equally legitimate. Moreover, no moderator and the long table etiquette shifts the responsibility for the shape of discussion to all its participants.

| Data | Czas | Tytuł | Miejsce | Wstęp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

June 15 2019

, 13:00-15:00

Saturday

|

13:00-15:00 |

The Right to School |

Special Schools Complex no. 89 | Registration is closed |